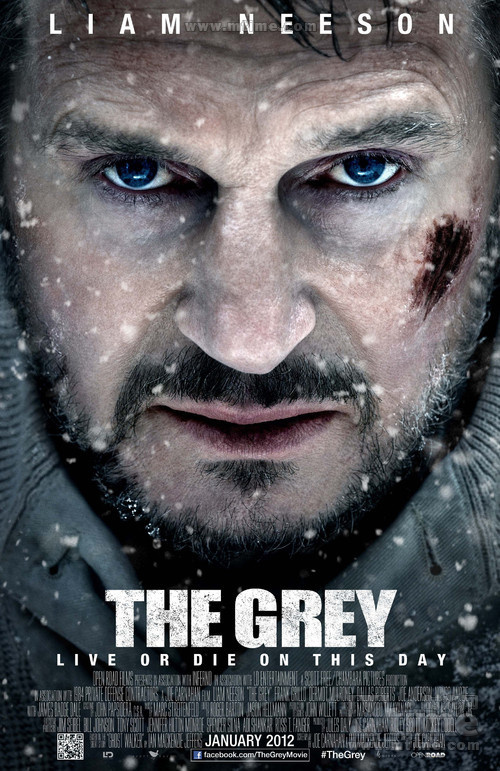

Liam Neeson has an impressive resume. Think about it. He trained Batman and Obi-Wan and Darth Vadar. He is both Aslan and Zeus (which makes him a god in at least two mythologies). And he single-handedly annihilated an entire human trafficking ring during a short vacation in Paris.

Having duly weighed this in our minds, we have to ask: Who or what is going to mess with a guy like that?

Wolves. And God.

Of Plane Wrecks & Mythical Beasts

In The Grey, Neeson plays the character of John Ottway, an oil-rig worker who survives – together with several other roughnecks - a brutal plane crash in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness. As if the subsequent injuries and harsh weather aren’t bad enough, the group soon discovers that they are being hunted by a pack of wolves.

And you thought your day sucked.

The movie tries to do several things, and ends up doing none of them very well. As a straight-up survival tale, it is difficult to take seriously due to its fantastical portrayal of the wolves themselves. These beasts are less a product of fact than they are the mutant spawn of an overactive imagination (and possibly an aggravated case of lupophobia). They move with ghost-like speed, show absolutely no fear of man, and seem to anticipate the characters’ every move with split-second precision. Generally speaking, they behave more like the Raptors from Jurassic Park than any creature you’ll find on the Alaskan frontier.

I’ve seen people object to this on the ground that it is “demonizing an endangered species.” I object to it merely on the ground that it is bad storytelling. Ottway and Co. may as well be running from dragons or maniacal tooth fairies for all the sense it makes.

A Hairy, Growling Spring-Board

It may be said that the wolves are deliberately exaggerated because they represent, well, other things. The inevitability of death, perhaps. Or bad choices. Or a violent cosmic joke played at the expense of our heroes. Take your pick.

To an extent, I agree. It’s clear that the wolves are meant to be more than wild carnivorous mammals. They also serve as a catalyst for introspection among the characters - a hairy, growling spring-board to existential discussions about life and death and “what it all means.”

It is here that The Grey attempts to throw us some psychological drama and a hearty chunk of philosophical pondering. I say attempts, because the whole thing is far less profound or intelligent than it wants to be (or seems to think it is). Any psychological drama is blunted by the fact that we never get to know any of these characters very well. This isn’t for lack of trying on the cast’s part, but the script doesn’t give anyone much to work with. It’s pretentious, simplistic, and saturated with enough profanity to make Kevin Smith grin his little head off. I’d call it “philosophy with a side of F-bombs,” but closer to the truth is “F-bombs with a side of philosophy.” And the philosophy is anything but nourishing.

Repeated throughout the film is a bit of poetry that reads like a flagrant rip-off of William Ernest Henley‘s “Invictus”; which, if you haven’t heard it, goes like this:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll.

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

There, in sixteen bitter lines, the philosophical agenda of The Grey finds an apt summary. By the end of this grim and punishing ordeal, the message is unmistakable: God – if He exists at all – is a cosmically indifferent jerk of a deity, and we should hate His guts for that. Life sucks, and our fate is up to us. Grin through bloody teeth and bear it.

The Anti-Job

The story here reminds me, in certain distinct ways, of the story of Job. In both cases, we find a man stripped of everything and plunged into a nightmare of affliction. In both cases, we find a man who wants to know “where God is” in all this misery. The great difference lies in how each story ends.

Job: “I will lay mine hand upon my mouth. I repent in dust and ashes.”

Ottway: “F**k it. I’ll do it myself.”