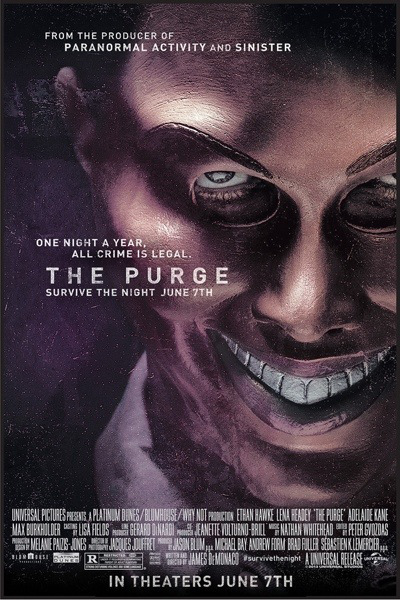

What if one night out of every year, the authorities declared all criminal activity completely legal? What would you do? Steal the car you’ve always wanted but never could afford? Plot the death of your boss because he’s such a royal pain to work with?

In a futuristic America beleaguered by crime and overcrowded prisons, the government has sanctioned just such a night — an annual 12-hour period in which any person may commit any crime (including murder) without fear of retribution. Hospitals are shut down. Rule of law is suspended. This night of nights, you are allowed — nay, encouraged — to do literally anything you want.

Or not. Maybe you’d rather avoid the blood-soaked pandemonium outside. If so, feel free not to participate. It isn’t mandatory. Just bolt your doors and lock your windows… and hope to God you haven’t made any enemies in the past 364 days.

Wasted Opportunity

Preposterous or no, the central conceit of The Purge is a king-size intellectual playground. What a shame, then, that director James DeMonaco never roams very far beyond the kiddie slide. Given the chance to explore a variety of important questions about violence and ethics, he barely acknowledges that these even exist. For a movie concerned with something as dangerous as human nature, The Purge is entirely too safe.

DeMonaco’s story introduces us to James Sandin (Ethan Hawke), a security salesman who lives with his family in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in LA. When a stranger takes refuge in the neighborhood during the yearly lockdown, trouble isn’t far behind — and by trouble, I mean a small mob with masks, guns, and machetes. In less time than it takes to say, James is given a very simple ultimatum: surrender the fugitive or die with him.

As a home-invasion thriller and as social commentary, The Purge is insipid. I mean, we have a problem on our hands when a movie’s trailer is arguably more gripping than the movie itself. Seconds lengthen into minutes, the body count rises, but meaningful character development never shows up. Neither does anything like an intelligent sense of pacing. The film moves from one act to the next with all the grace of a crack addict.

During a conversation with his son Charlie, Mr. Sandin explains that the Purge “allows people a release for all the hatred and violence that they keep up inside them.” Charlie then raises the obvious question: “So why don’t you guys kill someone tonight?” The one answer Mr. Sandin can come up with is, “Because we don’t feel the need to.”

It’s a feeble response, and he knows it. Charlie knows it. We know it. For if right and wrong are to have any real meaning at all, they must find their roots in something else — something beyond what James Sandin or you or I or society as a whole may “feel” at any given moment. I kept waiting for DeMonaco to return to this subject, but he never did. He had already refocused onto more compelling stuff, like having one character drive a letter opener repeatedly into another character’s bullet wound.

The Real Crime

The movie begins with snippets of security camera footage, each giving a glimpse of the horrors committed during previous Purges. People are shot, stabbed to death, and pounded with baseball bats. Lots of blood, lots of bodies. The story goes on. More blood, more bodies.

To call it a crime spree would be a woeful understatement.

But maybe the worst crime of all — the real crime — is that out of an idea with such overwhelming promise came a film as underwhelming as this one.